Marcia Pradines: Chesapeake Marshlands NWR

The Chesapeake meets its shoreline abruptly in some places, but at Blackwater its almost unnoticeable. Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge is a meshwork of water and land where mere inches in elevations can mean the difference in miles between open water, tidal flats, low marsh, high marsh, and forest, each with their own distinct ecosystems.

““Hearing the sika bugle in the morning, evening, or the middle of the night — it makes your hair stand up on your neck.””

This makes for perfect habitat for an array of wildlife, and most famously for bald eagles and waterfowl that the refuge was originally created to protect in 1933. But perhaps the most interesting and unique of its residents are sika deer, also known as the “ghosts of the marsh.”

Sika are a species of elk originally from Japan introduced to the area by a Tidewater family more than 100 years ago on James Island on the mouth of the Little Choptank. The island has all but been claimed by the Bay, the but the sika migrated to the mainland, where they hide out in the marshes of Blackwater and southern Dorchester County.

Sika are one of the many species that Marcia Pradines manages as project leader of Blackwater and the three other refuges that collectively form the Chesapeake Marshlands Wildlife Refuge complex. In this role, she oversees all management responsibilities of the refuges, including hunting and fishing.

I caught up with Marcia recently at the end of February deep freeze to hear about the different seasons at Blackwater and to get some clues about the elusive sika. My questions are in bold below, followed by her answers.

What is your role with Chesapeake Marshlands National Wildlife Refuge?

I'm the project leader of Chesapeake Marshlands NWR complex and oversee a series of refuges in region included in the complex. Blackwater is by far the largest and the one that most people are familiar with, though I’m also responsible for Eastern Neck NWR, Martin NWR on Smith Island, and Susquehanna NWR. Both Blackwater and Eastern Neck are open to the public.

Marcia with a nice spring gobbler

We have 20 people on staff, including biologists, park rangers, maintenance, law enforcement, and admin, and we all work together to support this complex of refuges, and coordinate with different teams, strategies, and partners. We host nearly 200,000 visitors each year, who like to observe wildlife, bird, hunt, hike and just enjoy from their cars.

Do you work with the state and DNR too?

A very important part of conservation is our work with partnership — it’s absolutely critical. We work with the Maryland DNR, who helped us with the Mid-Winter Survey, Ducks Unlimited, National Wild Turkey Federation, and Friends of Blackwater, to name a few. As our budgets decline across the National Wildlife Refuge System, the more critical partnerships become.

Blackwater is known for its waterfowl and eagles, but it also has a famous resident in the sika deer. What exactly is a sika deer, and are they are hard to hunt as I’ve heard?

It’s the only place in the country — in the world — that you’re able to hunt this subspecies. The same subspecies is found wild only on an island in Japan.

One thing I've learned from learning to hunt them is that once you think you understand them, you don't! They breed earlier than whitetail — October is the peak month. During the rut, they're bugling just like Rocky Mountain elk, getting their harem, establishing their territory. They love the phragmites. They spend much of their time in the marsh and use the phrag as both cover and food.

You can walk right past them, and not bump them — they’re not like whitetail in that respect. When it’s frozen or high tide, they’ll move to the woods. They like to bed in the holly and myrtle or any cover. What I’m surprised about is the lifespan. A 15-20 year old sika is not uncommon. They’re also more nocturnal than whitetail, especially after gun season when they feel pressure even more.

Are sika more clever than whitetail?

Ghost of the marsh

I’d say they’re different than whitetail. Everything I know about deer from learning to hunt whitetails in Ohio seems to be different than sika. And they are an elk, so this shouldn’t be a surprise. They’re not smarter necessarily, but different. Scent is not as big of a deal, and scent is everything for whitetail, so you can get away with more that way, but their eyesight seems stronger. Their eyes on more on the front of their head.

When going into the stand, they sometimes tolerate more noise too. They just think differently. They spend a lot of time in marshy, wet habitats, and love water. In the woods, they’re more likely to follow ditches. They like to keep their feet wet! Of course they don’t like it when its not completely frozen as its hard to traverse, but who likes that?!

How big is the sika population?

We don’t have an exact number but MD DNR estimates about 10,000. Many live in or use parts of Blackwater but we have private land interspersed, and they’re always always moving. Dorchester is the main county you can find them in, but they’re moving to Wicomico and along the Marshyhope Creek.

Actually, this past September, we did a population density survey with University of Delaware, using hand-held flir infrared devices to get an estimate of population density in terms of habitat. We worked with the world’s foremost sika expert, Dr. Jake Bowman. We’re trying to get a valid, statistically robust survey. We spent all September, from 3pm to midnight each day using the infrared device, and it penetrates where they’re hanging out. This will provide us with a baseline to determine impacts of any changes to hunting on the refuge. The results will be shared at our public hunt meeting on March 24 from 10am-12pm at the Refuge Visitor Center.

I know Blackwater has a lot more wildlife beyond sika. What do the different seasons look like on Blackwater, and what kind of critters can you see, hunt, or fish for through the seasons?

Spring

Starting with spring… most of the waterfowl are going to remain on the refuge through early March. We see lots of concentration of geese, and also eagles - the Eagle Festival is on March 17. People love to see the eagles! The osprey also come back in the spring, right around St. Patty’s Day. The eagles often outcompete with the osprey, stealing their catches. You may spot one of these aerial battles off our Wildlife Drive.

The impoundments are drawn down in spring, and we’ll start getting ready for planting crops, managing our impoundments, and start preparing the soil for summer. We have 360 acres of impoundments that we manage for wintering waterfowl. The goal is to encourage native plants like smart weeds, and supplement native foods with agricultural crops like corn, winter wheat, clover, and milo.

As we say goodbye to our overwintering waterfowl, but we then have nesting eagles, migratory shorebirds, and forest-interior songbirds returning. And for hunting we have turkey season of course! We have a lottery system for a limited number of turkey hunters, and people can hunt on Tuesday and Saturdays in late April and early May.

People will fish off Key Wallace bridge for perch, and people are coming more to fish for snakeheads. They get them when they’re spawning on big top baits like buzz baits, spoons, flashy lures, but its only when they’re spawning. You’ll also hear the chorus frogs and spring peepers in the evening, my favorite sound in nature.

Summer

Summer is the quiet time time at the refuge and great for hiking the trails, paddling, stand-up-paddleboarding. You might see otters swimming by or muskrats, and there are still local waterfowl and eagles and osprey. Of course we do have pretty bad mosquitos!

We have about 30,000 acres, with 1/3 marsh, 1/3 open water, and 1/3 forest, and that’s where you can find the Delmarva fox squirrel, along with songbirds and owls too.

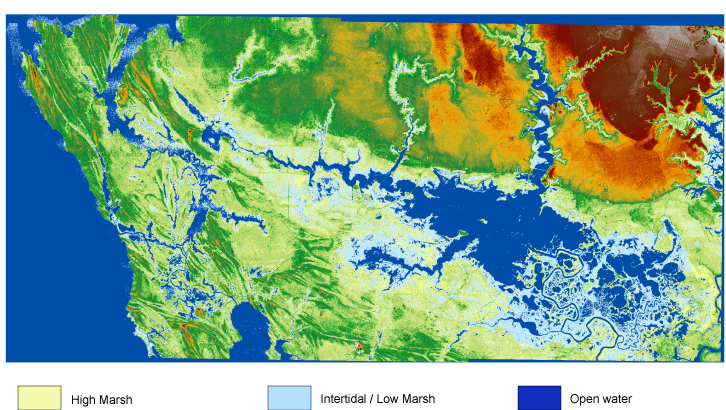

USGS map of Blackwater

The Delmarva fox squirrel?

The Delmarva fox squirrel was removed from the endangered species list in 2015, and are now found in 10 counties on the Delmarva. They are common on the refuge and nearby private lands where the required open forest habitat has been restored. This is a great success story of recovery just like the bald eagle, also delisted from the Endangered Species list. They are the biggest squirrel you’re going to see, and spend more time on the ground. If you see it sitting next to a grey squirrel, they [the Delmarva fox squirrel] are a much heavier, bushier squirrel, and not as acrobatic. The Delmarva fox squirrel is a much lighter grey with some white, than the more common grey squirrel.

Fall

Fall is when it starts getting exciting. We’re managing the crops for the waterfowl, which start coming in. The teals are the early migrators, mallards move in, and black ducks start coming in for the winter, which you can see right from Key Wallace Drive. Later on the pintails and geese come in larger flocks in November, and the swans are pretty late into December. They’ll loaf in the impoundments as it get colder and colder, and feed along the Key Wallace corridor where visitors can easily observe them.

Archery starts September 8 [for whitetail and sika], and that’s a great time to be in the refuge. The rut starts pretty early for sika — in October. I’ve heard them bugling in September, but mid October is when the rut really peaks, and that coincides with the early muzzleloader season. Hearing the sika bugle in the morning, evening, or the middle of the night — it makes your hair stand up on your neck. They sound a little bit like elk, which of course they are.

Fun thing about hunting for deer is that you can focus on the sika rut in mid-October, and as soon as that is over, focus on the whitetail rut in mid-November. We have all of the seasons for deer: archery, early and late muzzleloader, and also shotgun. Last year [2017-18] hunters harvested 373 sikas and 95 whitetail.

Winter

We offer a waterfowl season in the complex — early season is off the Blackwater River, and then the late season is off the islands. We had a hard winter this year, and 13 white pelicans actually spent the winter here with us. They huddled up with geese. You could see a group of Canadas with a shivering white pelican mixed in. They refuge is important for the geese to have for the winter, and also the food that is provides. In December they’ll move to a milo field, and they’ll be in the corn when it gets really snowy once they knock it down. After the Canada goose season ends, we knock it all down so get they a late-season boost before migrating back north.

Do you keep any harvest records or surveys of your waterfowl?

For deer and turkey, we have harvest surveys reported through the state — we don’t have that for waterfowl but we do have a sense of what the waterfowl populations are thought several things: We do a weekly waterfowl count with our biologists each week from November to March. That just gives us a snapshot in time, and the numbers can change week to week.

We do know that 10,000-12,000 are on the refuge through the winter. We also do an aerial surveys in mid-winter — two to three between December and February — with a fixed-wing planed. We also conduct a mid-winter eagle survey. We usually count about 200 eagles but this year it was lower because the open water was frozen and eagles of course then can’t hunt for fish.

When I interviewed Jake McPherson at DU, I asked him which parts of Maryland have concentrations of different kinds of waterfowl like Canadas, black ducks, or cans, and he joked that he would spare me a shooting match among my readers about how great hunting is in Easton vs. Chestertown! Do you want to give it a shot? Do you see more or less of different waterfowl species at each of your refuges?

Martin National Wildlife Refuge has everything — sea ducks, all kinds of scoters, and a tremendous variety of ducks. Eastern Neck has a huge concentration of swans and ducks, and you’re able to see them all very up close from the Tubby Cove boardwalk and other trails. Blackwater has over 10,000 waterfowl, and the trends have been rather steady. Numbers are declining all over the state but over the refuge it’s been pretty consistent. It varies by weather conditions of course…

But I’m going to dodge it! I know I dodged it ha! But honestly, they move across the landscape, and need these different places at different times.

High marsh and low marsh can be inches and worlds apart

What major changes have you seen or are seeing in the lands you manage?

First, the bad one: We’re losing a lot of marsh to open water. With sea level rise, we’ve lost about 5,000 acres to open water since 1930. We’re going to see more ghost forest with dead trees with the influx of saltwater, and the marsh that is coming in is not the same. Instead of marsh grass, its phragmites and only phragmites, with not a lot of diversity. The silver lining is that the marsh is migrating upslope and we don’t have much development such as malls or natural features like cliffs to stop it. But we’re going to have to manage this marsh migration and decide where we protect and how.

The good news is that we have not had a detection of the invasive nutria for over two years. This giant rodent was introduced in the ‘30s and essentially ate out the marsh, hastening the process of marsh loss to sea level rise. Some estimates were over 50,000 but through a partnership with USDA that focused on removal through trapping and now they use dogs to monitor the watersheds and assure we haven’t missed any, which is possible. The nutria ate away at the marsh, so it’s a big victory getting rid of them.

Nothing better than spring turkey

Lastly, do you have any favorite traditions?

It’s not so much a tradition, but what I love about the outdoors is always finding the next challenge. I grew up fishing, and taught myself how to trout fish, and then when I was in my twenties I discovered fly fishing. And then it was going from stocked trout to wild, and it was always asking, what’s the next challenge? I didn’t start hunting until my early 20s, but I got to gun hunt in beautiful white-tail country in Ohio. Recently, with my move to the Delmarva, I also discovered archery, and have since been focusing on bowhunting. So it was always, what’s the next challenge?

What I did this year was get into turkey hunting, which may be my favorite. I’d always heard people saying how much they love it, and wondering why is it so addictive and so fun? One, it’s so interactive calling them in. I love that, and also being able to help call one in for friends. Its so challenging and their visual acuity is so stealthy. And two, the season. When you start, the leaves are off the trees, and then you see the buds, and by the end, it’s full spring. The wood thrush will come through in May, which weren’t there when you started. It’s like you’re greeting the coming of spring!